I bought an old Paris Review specifically for the purpose of reading an interview with Italian author Elena Ferrante, conducted by her publishers. This issue came out in spring 2015, at the height of her popularity from the Neopolitan novels, Ferrante’s expansive story of a female friendship spanning decades and four volumes, published between 2012 and 2015.

Publicly, no one knows who Elena Ferrante is. Ferrante is her nome de plur, a pen name, and when this interview was published, there were many theories, one, of course, that she is a man1, along with an exposé of her true identity, something I refuse to read. I actually don’t know if that is true, and I have no interest in either finding out or giving it legs on the internet. Why ruin a good thing, something that is actually meaningful to me. Maybe the writer’s identity has been revealed now, I don’t know. I have accepted the mystery. I love it.

The first Ferrante book I read was Days of Abandonment, around 2008. I bought it at Word bookstore in Greenpoint. It was one of those unplanned days at the bookstore, I was up for anything. I picked it up from a display of Europa Editions on a table. I didn’t know anything about the author or the publisher or book.

Days of Abandonment is the story, the brain, of a woman whose husband leaves her for another woman. She is left with their two children and the dog. An unflinching text, I read it in two sittings, needing to take a break from its intensity, the rage, the contempt. Joyce Carol Oates wrote a blurb, saying she read it in one sitting, and I can’t imagine how that must have felt, maybe like reading underwater with a giant stone on your chest. I needed to come up for air. Ferrante’s writing creates a physical response in me, beyond the identification, a panic, an overwhelm.

I read more of her books, what a place to find myself, and the people around me, in these complex characters. There was something about the places they go, places I’ve been. Years ago, when I started to see people on the train reading My Brilliant Friend, the first Neopolitan book, I was miffed.2 What did they know of her? I was there! She was mine. How dare they?

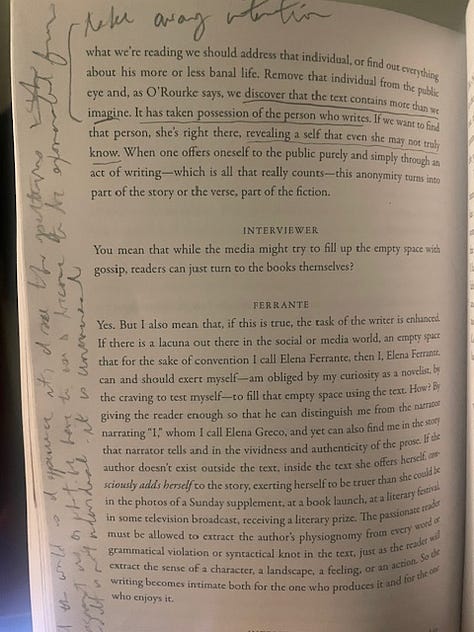

It took some time for me to have enough space to separate this new popularity from my time with Ferrante, when I could read the Neopolitan series without untoward outside influence. I didn’t want to ruin my personal connection with a trendy talk about a book everyone was reading. I think we all know people kind of ruin everything. That relationship is with her text, as she famously refuses to be public. The Paris Review interview broaches this subject, along with her process.

Interviewer:

Before you made the decision to write anonymously, had you been censoring yourself?

Ferrante:

No, self-censoring doesn’t enter into it. I wrote for a long time without the intention of publishing or having others read what I was writing. That trained me not to censor myself. What I mean is that removing the author-as understood by the media-from the result of his writing creates a space that wasn’t there before. Starting with Days of Abandonment, it seemed to me, the emptiness created by my absence was filled by the writing itself.

I long for a different interaction, one I know exists because I’ve lived it. A quieter, more focused place, a different space in my brain, that’s why I’m reading this interview so very slowly. I keep losing my place, going back over pages I’ve already read. I’ve started underlining (with a pencil, with a pencil!) phrases that strike me, but at any moment, it is any sentence, any utterance, a truth I could feel but hadn’t had words for, but the inklings, the shadows of it have moved though my brain. I luxuriate, a word in and of itself luxuriating with all of its syllables, in this interview, in having words be put on feelings and a meaningfulness I have missed.

Interviewer

You’ve mentioned disappearance-it’s one of your recurring themes.

Ferrante

It’s a feeling I know well. I think all women know it. Whenever a part of you emerges that’s not consistent with some feminine ideal, it makes everyone nervous, and you’re supposed to get rid of it in a hurry. Or if you have a combative nature…if you refuse to be subjugated, violence enters in.

How much of my time has been wasted, performing for others, making them feel comfortable, compromising myself? There’s a fine line, or maybe it’s a giant swathe, between being considerate of others because they are human beings with feelings and how we treat each other is a vital cornerstone of society, versus being performative to make people feel better, trying to be more palatable, and heard in the process. I’ve never been accused of playing nice or being anything like that, I’ve got no poker face. Yet I know I have been diminished, I have accommodated more than I want to, and through that I have been lost, some portion of me is gone.

And that is one reason, or many of them, why I’m drawn to Ferrante. I’m lured by her writing, where I’ve found myself and so many people I know and where I grew up, and also her seemingly personal absence, her refusal to give us what we want just because we want it. This is a recalibrating thought. For myself, for what I give of myself and put out there, for what I want and/or expect from others. And just the wanting in general, what it masks. In a world where we herald the inability to be satiated, wanting more and more, consuming image after image, mistaking it for a voracious appetite and search for truth. Maybe this consumption is just for the sake of consumption. To pass time. To escape the brutal reality of this world. Maybe it’s all avoidance, a distraction.

Perhaps we’re not satisfied because none of this is satisfying. We can’t fill up on emptiness, it just can’t do it, no matter how vast and endless it is.

But when something actually sticks, when it lands, it’s fucking everything.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the importance of mentors, how we need them. They’re our beacons, a bright star. It’s so easy for me to see how I don’t want to live, who I don’t want to be, the world is full of those examples, I’ve been using them for years on what not to do. The people who show me the way, how I want to be, how I want to live, who I want to be, I notice. I read. I watch. Elena Ferrante, she’s up there. I don’t know what she looks like, and while it seems strange to emphasize this, the absence of her physical being to her work, it’s an important point, especially as our world becomes more and more shallow. Ferrante’s work. Her writing. The people and places and lives she chooses to share. That’s it. I get to read her words, her stories, and it is more than enough.

Ha!

I know, such a childish response. I won’t lie and say I’ve matured since.

What a superb essay (and such relatable thoughts). You have a gift for cutting through to the core of a thing.

Thank you!

Here’s to something that actually sticks, that actually lands.✅ Thank you, this is indeed fucking everything. Nailed it.