Raw Power

I bought Sinéad O’Connor’s debut tape The Lion and The Cobra soon after its release in November 1987, probably at Record & Tape Traders in Towson, Maryland. I read about it in Spin or Rolling Stone or Sassy magazine. Music then, before the internet, was found through word of mouth—a cousin, a friend, someone’s older sibling, a babysitter, the cool person at the record store, a magazine, a film soundtrack, a video on MTV or an award show performance. A mix tape could blow up your life, in a good way. We traded in the tangible, real life, cassettes, LPs, shows, they were our algorithms.

I spent a lot of time with that album driving myself between school and jobs, and winding country roads for fun, smoking Marlboro Reds, screaming along. A few years ago I came across another copy, a tape even! and played it in my truck with a tape player. The decades have passed, the lyrics are indelible to my mind, every single word, the sequencing, every pause, the phrasing. I didn’t consider O’Connor a major influence in my young life until this reacquaintance. That’s happened a few times with certain bands, ones I don’t consider formative until I realize I know every word to every song. I’m not talking about nostalgia, this isn’t wistful pining for youth. This music makes up part of me, late nights, early mornings, time spent on in cars, porches and bars and bedrooms gathered around a record player. I’m not reliving something, I’m remembering myself.1

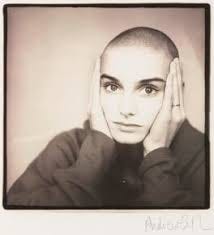

Sinéad O’Connor2 called her own shots. She fired the producer the record label hired for this album and ended up co-producing it. It didn’t feel like anyone was watching over her (save Kris Kristofferson) or making her decisions—to shave her head right before her debut album, to dress in jeans, bras, leather jackets and combat boots, to boycott the Grammys when she was nominated for four, to rip up her mother’s picture of the Pope John Paul II on SNL. Many of the other female singers and bands I gravitated towards were cool, they wore their styles like armor. If you’re cool, no one and nothing can touch you—Blondie, Joan Jett, Siouxsie Sioux, Exene Cervenka—stone cold aspirations. Sinéad O’Conner was not cool, she was too openly vulnerable.

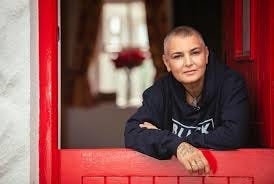

I’ve shied away from vulnerability for most of my life. I needed to be hard in the world, even as a kid. Especially as a kid. I made the cardinal sin of being fat, my body too big to be acceptable in the female canon of attractiveness. So I couldn’t be both sensitive and fat. That would be too much. Listening to The Lion and The Cobra was like staring at the sun, a catharsis I badly needed. Sinéad’s rage and rawness abound, she lived without a safety net. Her face, her gaze, offers such clarity and openness that lasted her entire life, up until her death at 56 years old last week.

Sinéad O’Connor lead with her heart, regardless of the pain it caused her. We left her out there. She believed money was the root of the human race’s problems, she told Arsenio Hall on his show when they talked about her Grammy boycott, “we are concerned more about money than we are about each other.” She spent her whole life trying to make these connections with and for us.

I’ve been heartened, and surprised, by the breadth of outpouring, sentiments and coverage about her since her death. I don’t tire of reading about her and her influence. Hanif Abdurraqib in his New Yorker piece “Sinéad O’Connor was Always Herself” writes

“The culture in some ways has caught up to her—about the hyper-commercialization of the Grammy Awards, the role of the national anthem before concerts or sporting events, and, most notably, the epidemic of abuse within the Catholic Church.”

Maybe next time it doesn’t take thirty years for us to catch up. I doubt it, the research doesn’t support it.

I listened to the tape with my partner in the car. I was singing “Just Like U Said It Would B” at the top of my lungs, same as when I was 16, when I realized this activity was best enjoyed alone.

O’Connor converted (‘reverted’ in her words) to Islam in 2018 and changed her name to Shuhada Sadaqat, using her previous name for performances. For the nature of this essay, I refer to her as Sinéad O’Connor because of the time period of the material and that I am discussing her as a performer. “I’ve been a Muslim all my life and didn’t realize it,” she said in a 2019 interview on the Irish TV show “The Late Late Show.” “The word ‘revert’ refers to the idea that if you were to study the Quran, you would realize you were a Muslim all your life and you didn’t realize it. This is what happened to me.”

I too was a fat kid who was looking for emotional connection in music, and I too felt back then like something about her was "too angry." Part of it was probably my internalized sexism and now I realize (thanks to you) a big part of it was her vulnerability that scared me. And only recently, I really started appreciating how she could be so vulnerable even from the time she was preciously young and beautiful. Thank you.