After living on my grandparents’ farm for a year, I was involved in 4-H from the ages of 11 to 17. I took to farm life, to the cows, the work, my first foray into how sheer exhaustion shuts the brain off, a beautiful result of hard labor. 4-H is a pretty common club for kids in the country to be a part of, although it’s not just for farm kids. It’s not a Christian group, thankfully. The title of this essay, “To Make The Best Better” is its motto, and the 4 H’s are head, heart, hands and health. People choose programs based on their interests, it’s not all animal husbandry, but livestock is the most popular activity. If you’ve ever walked through the animal stalls or exhibition hall at a fair, most of those entries are by youth in 4-H. My Uncle Kenny was a dairy farmer who coached the Baltimore County Dairy Judging Team. My activities were dairy cattle, dairy judging and marksmanship.

Dairy judging is the attempt to understand the investment in a cow based on her appearances. It’s the basis behind who gets the blue ribbon and who doesn’t and is behind purchasing decisions at cattle auctions and how animals are bred. Dairy judging analyzes the structure of the animal, and all the animals in the group, ranking them accordingly. There were competitions for 4-Hers, and their redheaded stepbrother the Future Farmers of America, at county, state and national levels. A ranking of the rankers, if you will. I was very good at dairy judging, eventually competing on the national level.

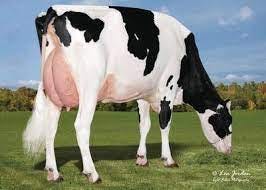

Dairy strength is one of the most important aspects of these evaluations, the term refers to the general look of a cow, from her muzzle and neck to pins and dewclaw, a mixture of the evident physical strength of the cow with an angularity indicating high milk production, meaning that what she eats converts to milk. The term “dairy” also indicates a feminine quality, pretty basic shit like is this cow pretty? The concept of cleanliness is about the neck, withers, hooks, flanks and ribs, if they are lean and angular but not frail. Strength is paramount, shown by the span of her chest floor, the depth of her fore and rear ribs and width at the pins. It tells us if she has room for her organs, along with the work of producing milk and birthing.

Legs are also important in these evaluations, considering how much time she will spend on them and some of it will be on concrete, enemy of all feet. Are they sickle-hocked or too straight, or just right, with just enough angle, almost akin to our own legs, we all need a little bounce in our knees. Does she have a strong hoof with a steep angle? That’s good. Do her front legs buckle? That’s bad. Essentially the evaluation of the legs and feet tell us if they can carry this body.

Then to the udder, the attachments so vital, both rear and front and the median suspensory ligament that runs down the middle. The teats should be plumb to the ground and spaced evenly, nothing wacky here, the quarters balanced and evenly filled. The higher the udder the better, that’s why the attachments are so important, lingering around or above the hocks depending on age. Jesus Christ I’m turning 50 this year1 so this particular section of breaking down of a female body is especially poignant. Fuck, it all is.

Her frame should be tall and long and wide. A beautiful birthing and milking creature that is an excellent representation of her breed-whether it be Brown Swiss (very tall, sort of a dreamy brown gray sometimes with black accents), Holstein (the most popular cow in the US, the classic black and white breed), Guernseys (light red or beige and white, their milk is golden in color because of its high rates of carotene), Ayrshires (rust and red and white in color, a bit strong-willed) and Jerseys (the smallest breed, fawn and black and brown and white with high percentages of fat and protein in their milk). Dairy judging is completely impartial and totally not.

I understand now how I was drawn to it, after living with my brain for this long. Dairy judging is analytical, balancing the logistics of a body against the logistics of another body. You try to see the future of the heifer and the cow in her legs and udder attachments, maybe this is the start or continuation of a good line that will help your farm. That’s what it’s about, keeping the farm. It’s also not lost on me that this could be a feminist allegory about the gaze. Sometimes it is, but there’s an important element of utilitarianism, of trying to understand the body, that fascinates me.

I was good as seeing cows, that’s the term for it, which earned me begrudging respect from my peers, aka teenagers who grew up and lived on farms all the time, who milked cows every day. I didn’t. I lived in the suburbs with my divorced mom and sisters. I was an outsider, and my taste in music and fashion choices duly expressed this. I bought Jesus & Mary Chain and Cure t-shirts out of the back of magazines, maybe my hair was shaved. One morning, before dairy judging practice, I translated lyrics from David Bowie’s “Changes” into Russian and wrote it on a white t-shirt with sharpie. I wore it to even more rural Maryland. I was weird, but I could see cows.

Dairy judging practice occurred throughout the summer, leading up to the weeklong Maryland State Fair, ending on Labor Day. These practices were important, a few at county fairs and others at farms in different counties. The goal was to see all the dairy breeds, most farms focus on one breed.2 It was also social, especially without school. Summertime meant more work, literally making hay while the sun shines. We’d go after morning chores, travel to the farm, practice, eye each other and barely feign social skills, then return home for evening chores.3 Lunch was always at McDonalds, a real treat.

The summer before my senior year of high school, I placed in the top ten for dairy judging at the state fair. Two days of intensive judging followed to figure out who would go to Madison, Wisconsin for the World Dairy Expo, the top youth judging competition in the country. The second team goes to North American International Livestock Exposition in Louisville, Kentucky. I was on the team that went to Louisville in 1988 and placed first when I was 15.4 What I miss most about that trip was the shiny red satin jacket with my name embroidered on the front and our sponsor’s name “Sire Power”5 in large white letters on the back. We placed first at Louisville.

This time around I was hitting my stride at the right time. Previous years, since Louisville, I peaked too early in the summer. Dairy judging competitions consist of classes that you rank, always 4 heifers or cows, organized by breed and age, each 15 minutes long. The cows walk in a large circle for a bit, then they stand. The art of showing a cow is another topic entirely. You can’t touch the cows. You stare at them, picking them apart, trying to rank them. At the end of the class you hand in the decision to your coach and the next class begins.

Then there are Reasons. I capitalize this, as Reasons is not just a noun or a verb, it is a verbal defense of the ranking of a class and this is its official title. Two classes are designated for Reasons, entailing copious note-taking, somehow always a small sheet of paper with a tiny mini golf pencil. The animals still graded, it just meant later we had to memorize why we placed the class the way we did, revisiting barely legible scribbles to make the case, and present the argument to coaches during practices and judges during competition. There was definitely an austere presentation aspect to it, probably similar to farmers presenting to a bank to get a loan. That’s just good practice.

I was good those judging days, real good. I was going to make it to Madison, I was going to be in the top four. But this thought kept nagging me and I couldn’t shake it. Was I going to be a farmer? Was I going to apply to Virginia Tech for Dairy Science, and keep doing this thing, this thing I cared about and that I was good at, or did I care about it because I was good at it? Some days I can’t tell the difference between them, not just for cows but for everything. Was this going to be my life? From what I could tell, once you were in that was it, there was nothing else but the farm. Was I going to take a whole week off of high school my senior year to go to the Wisconsin to be at the world’s largest dairy-focused trade show? That was a big deal for me. I didn’t miss school, I needed scholarships.

I dropped out of the competition. My spot went to Randy Stiles, who in college, had very nice hair and was from a storied Jersey family farm. He thanked me for a few years to follow, knowing that’s the way he got on the team. That Maryland team placed first at Madison and then went on a free trip to Europe to judge cows over the summer for a few weeks. Europe. Where you are allowed to touch the animals.

September 1.

Many farms, especially today, do not just have one breed of cow. More traditional farms do.

Oddly enough, we never wore chore jackets to do feed and water the animals and milk the cows. T-shirts, hoodies from the grain store, barn jackets, yes yes yes. Flannels. Yes. Chore jackets. No.

I couldn’t remember how old I was at Louisville but I do remember being tormented by the Beach Boys song “Kokomo” on every radio station repeatedly. The year was 1988.

Sire Power was a semen mail-order company. Semen is chosen based on the bull’s physical attributes, sometimes with a specific cow in mind to artificially inseminate. I gave this jacket to an old friend who no longer has it, so he says. If you happen up on it in a thrift store between here and Ohio pick it up for me please.

My favorite Substacks are the Substacks where I Learn Things, and this has delivered in spades. Thank you for your service!

“Was a contender” Could picture you on 50’s Hoboken rooftop crowned by Basquiat!